After a brain injury, a person may find communicating more challenging. This includes speaking, listening, reading, writing, and understanding language.

Topics in this section include:

Aphasia

Aphasia is the term used to describe a language disorder. It is a common language problem that occurs after a stroke (which is a non-traumatic brain injury), but can occur from other causes such as traumatic brain injury and tumours [1]. Aphasia can impact your ability to talk, understand conversation, and read and write, which are all important aspects of communication. Someone with aphasia is often able to understand others or know what they want to say, but has difficulty putting thoughts into words or grammatical sentences. Difficulty communicating because of aphasia can lead to social isolation and be associated with lower quality of life [2].

Aphasia can range from mild to severe and can be categorized into several types. Working with a speech-language pathologist to understand your specific pattern of impairments and areas of strength is important. This can help to create your therapy goals and find the most effective ways to communicate with others.

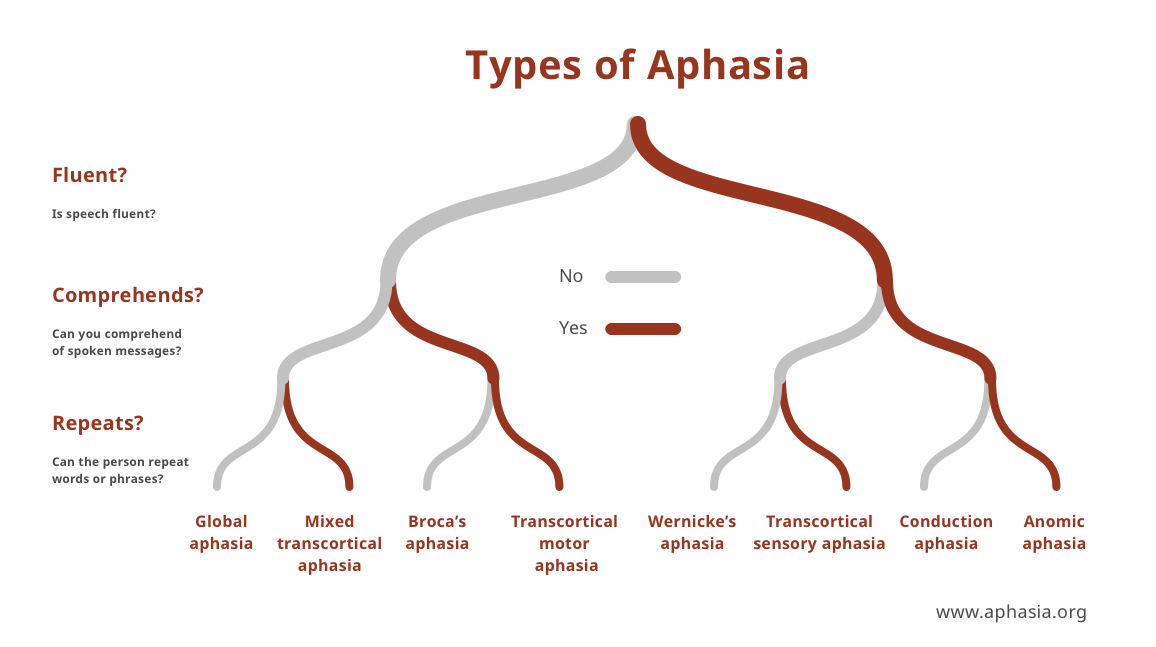

This chart from the National Aphasia Association demonstrates common types of aphasia based on patterns of impairments.

Please note that this diagram only shows a selection of types of aphasia. Since there are so many different combinations of language impairments, it’s important to work with a speech-language pathologist to address your specific needs. Speech-language pathologists are experts in the assessment and treatment of all different types of aphasia [3].

Tips for improving and supporting communication

No matter the severity of aphasia, communication challenges can be incredibly frustrating. Communication and social interaction are important parts of maintaining relationships and supporting mental health and well-being. Finding support, participating in therapy with a speech-language pathologist (SLP), and learning strategies to communicate with aphasia can help reduce the risk of social isolation and improve communication between family members, friends, caregivers, and health professionals.

Work with a speech-language pathologist (SLP)

A speech-language pathologist (SLP) specializes in helping people with language, speech, cognitive-communication, and swallowing difficulties. A speech-language pathologist can be consulted during the acute stage of recovery or at a later point in rehabilitation. Some people have even benefitted from working with a speech-language pathologist many years after their injury. Speech-language pathologists complete a comprehensive assessment, work with you to create a therapy plan, and help you work towards specific communication goals. It’s important to remember that recovery is different for everyone: while communication skills can improve over time, long-term difficulty communicating may persist [4].

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices and technology are potentially a great way to communicate more effectively. There are both low-tech (e.g. paper or communication boards) and high-tech (e.g. electronic devices) options. There are several applications for computers, tablets and smartphones that generate sentences, translate text to speech, and more. Speech-language pathologists and occupational therapists on the recovery team will be able to determine if an AAC device is appropriate for you (taking into consideration any physical impairments, such as reduced movement of one arm) and make recommendations that best suit your needs.

Be patient

It’s incredibly frustrating to struggle with communication, especially if you haven’t had communication problems in the past. Communication often improves over time and you can also learn adaptive strategies to make communication easier and more natural, but it takes time and effort. Give yourself a break and be patient.

Focus on one task at a time

Multi-tasking can be tiring, and it can divide a person’s concentration. Divided attention can make it harder to find the right words. When you want to read, write, or speak with someone, try to reduce distractions and focus on one task at a time.

Join a conversation group, participate in activities and volunteer to practice

The more you practice a skill, the stronger it gets. Communication is a big part of recreational activities and volunteering. There are conversation groups offered by different community centres, hospitals, and programs to help you practice communicating. Often times these groups can be facilitated by an SLP, or a trained volunteer. By engaging in those activities, you get an opportunity to practice your communication skills. You also get a chance to socialize with others and may have the opportunity to connect over a shared experience, which can support your mental and emotional wellbeing.

Use notecards or picture cards

Someone who has difficulty communicating may benefit from using notecards or picture cards to help communicate. They can be used to let a communication partner know your specific communication strengths and communication challenges. Written aids or pictures can also be used to communicate important information (such as your phone number and address), answer yes/no questions, communicate frequently used phrases, and help identify what you need.

Reading

Reading skills are a component of language. People with aphasia may have difficulty understanding words they are trying to read. Reading plays a large role in activities of daily living (ADLs), and aphasia-related reading challenges can impact a person’s abilities to enjoy hobbies, understand medical forms, and more. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) can assess reading skills and make recommendations for therapy to improve your reading ability. Some people find that increasing text size, reading slowly, reviewing what you’ve read, and using a line guide can help with reading. Following a stroke, visual deficits or impaired physical movement of the hand can also impact your ability to read and write; for these concerns, you can also work with an occupational therapist [5].

Writing

People with aphasia may have difficulty with written language, which could include: spelling words incorrectly, making grammar mistakes, or writing the wrong word. These impairments can make communication, hobbies, and other activities challenging. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) can help by assessing writing skills, focusing on various evidence-based therapy activities to target these skills [6].

Dysarthria

Dysarthria is the term used to describe a speech impairment where the nerves controlling muscles for speech are damaged. Just like aphasia, there are many different types of dysarthrias. One of the most common ways used to describe dysarthria is “slurred speech”. People with dysarthria may have muscular weakness, a smaller range of motion with their lips and tongues, difficulty controlling volume and tone, and problems controlling airflow. While dysarthria can happen on its own, it is common for people with dysarthria to also have some form of aphasia.

Apraxia of speech

Apraxia of speech is another motor speech impairment that can occur following an acquired brain injury (or may be related to another neurological condition). Apraxia of speech is related to problems with motor planning or organizing speech. People with apraxia of speech make errors in the sounds of the words they say and can have difficulty with their rate and rhythm of speech. Apraxia of speech commonly occurs along with aphasia [7].

A speech-language pathologist (SLP) can help you with your speech by creating an individualized therapy program specific to your impairments. An example of what this could include is: learning specific strategies, completing speech drill-based activities, or completing strength-based exercises. Your speech may not be exactly the way it was before you had your brain injury, but with time and practice, many people see improvements.

[2] Vickers, 2010 “Social networks after the onset of aphasia: The impact of aphasia on group attendance”, and;

Hilari & Byng 2009 “Health related quality of life in people with severe Aphasia”; the Aphasia institute

[3] National Aphasia Association

[4] Speech-Language and Audiology Canada

[5] Headway

[6] Headway

[7] Management of Motor Speech Disorders in Children and Adults (Yorkston, Beukelman, Strand, Hakel, 2010) and Duffy, J. R. (2013). Motor speech disorders: Substrates, differential diagnosis, and management (3rd ed.). St Louis, MO: Mosby